At COP29 in Baku, developed-country parties such as the EU, the US and Japan agreed to help raise “at least” $300bn a year by 2035 for climate action in developing countries.

The goal was welcomed by global-north leaders and presented as a “tripling” of the previous target for international climate finance.

Yet it faced a strong backlash from many developing countries, with some branding it a “joke” and “betrayal”.

Closer analysis of the goal and climate-finance data helps to explain this response.

Analysts have shown that the target is achievable with virtually “no additional budgetary effort” from developed countries, beyond already-committed increases.

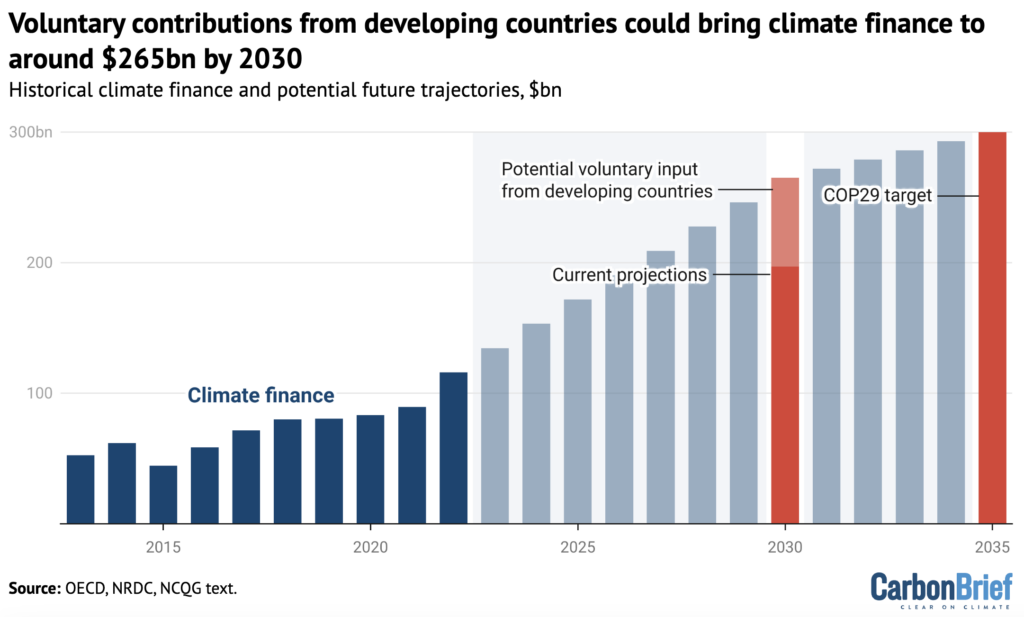

A combination of pre-existing national pledges and multilateral development bank (MDB) plans will bring climate finance up to around $200bn a year by the end of this decade.

Counting money already being distributed by emerging economies such as China — as “encouraged” under the new goal — could bring the total to $265bn by 2030. This could mean the target is well on its way to being met by that date, with minimal extra effort.

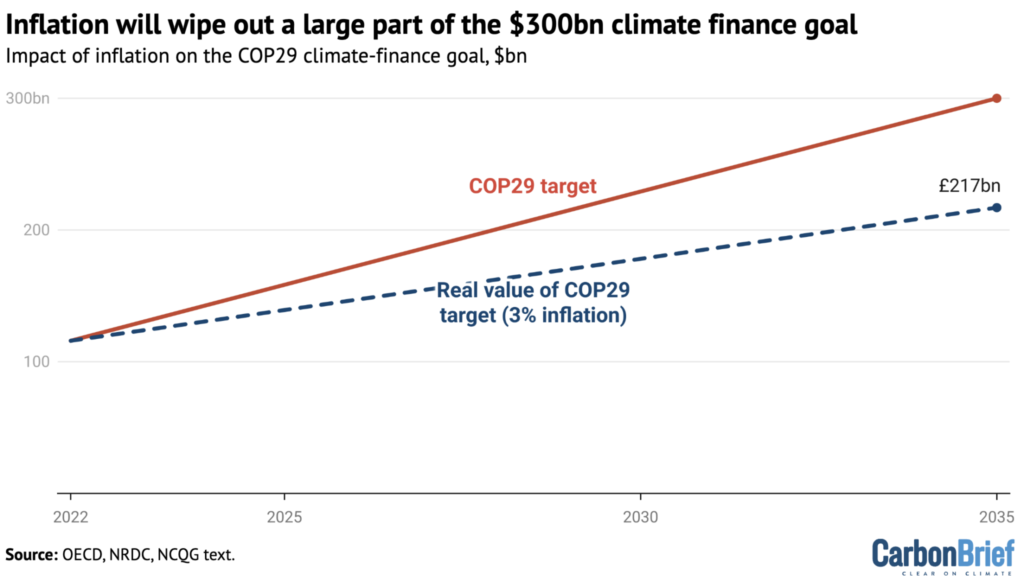

Moreover, as activists and academics have noted, the $300bn target does not account for inflation. When this is factored in, its “real” value could shrink by around a quarter.

The new target has emerged against a backdrop of financial strain and political uncertainty in developed countries.

At the same time, developing countries have stressed that they need climate finance to reach the “trillions of dollars” needed to cut emissions and protect themselves from climate change.

This article looks at three ways in which the $300bn goal could be met with little extra financial effort by developed countries — and provide fewer benefits for developing countries than the figure suggests.

1. Much of the goal will be met with ‘no additional effort’

The $300bn climate-finance target agreed at COP29 in Baku will be met with finance from a “wide variety of sources”, largely coming from developed countries.

This part of the “new collective quantified goal” (NCQG) for climate finance is likely to be made up of public finance provided directly by governments, as well as money from MDBs, specialised climate funds and private finance “mobilised” by public investments.

The wording of the $300bn goal frames it as an extension of the $100bn target. This was the amount that developed countries agreed in 2009 to raise for developing countries annually by 2020 — a goal that was extended through to 2025 by the Paris Agreement.

Beyond the central goal of $300bn, the NCQG also includes a much broader “aspirational” target of $1.3tn a year in climate finance by 2035.

However, this is harder to assess, as the text of the deal is vague about who will be responsible for raising the funds, which could include various sources that are beyond the jurisdiction of the UN climate process.

Developed countries and MDBs had already committed to raising their climate-finance contributions before a deal was struck at COP29, as noted in a joint analysis by the Natural Resources Defence Council (NRDC), ODI, Germanwatch and ECCO.

The collective impact of these pre-existing commitments can be seen below, with climate finance from developed countries set to increase from $115.9bn in 2022 — the most recent year for which data is available — to $197bn in 2030. This can be seen in the chart below, which does not account for inflation. (See: Inflation wipes out much of the increase in climate finance.)

The expected increase between 2022 and 2030 comes from a few different sources.

The analysts calculated that climate finance distributed “bilaterally” — as grants or loans via overseas aid and other public funding — was already expected to increase $6.6bn annually by 2025, based on existing pledges, bringing the total to $50bn. (The chart above assumes that bilateral finance remains at this level up to 2030.)

They also estimated that existing pledges and reforms at specialised climate funds, such as the Green Climate Fund and Climate Investment Funds, would add another $1.3bn per year by 2030. This would bring their contribution to $5bn.

The biggest increase that was already locked in before the COP29 deal was a pledge by MDBs — which provide 40 per cent of existing climate finance — to increase their contributions further.

A joint statement by the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and others in the first week of COP29 committed to raising $120bn of climate finance per year by 2030 for low- and middle-income countries. Of this, $84bn can be attributed to developed countries, based on their shareholdings in these banks.

On top of this, the climate-finance analysts estimated that $58bn of private finance would be mobilised by these bilateral and multilateral contributions in 2030 — up from $21.9bn in 2022.

The chart below shows the estimated breakdown, by source, of climate finance in 2030, compared to 2022.

These expected increases over the course of this decade mean that with “no additional efforts”, beyond what had already been agreed prior to COP29, developed countries would have been on a trajectory to reach around $200bn per year by 2030, and $250bn per year by 2035. (The latter was the first numerical target proposed by developed countries at COP29, which was, ultimately, negotiated upwards to $300bn on the final day.)

NRDC climate-finance expert Joe Thwaites, one of the researchers who undertook the Natural Resources Defence Council’s (NDRC) analysis, tells Carbon Brief that bilateral funding directly from governments is the “big constraint” in climate finance. COP29 came just after the re-election in the US of climate-sceptic Donald Trump and many European countries have cut their aid budgets. Thwaites says: “The MDBs are growing and doing all kinds of reforms and getting bigger and better, but the bilaterals are what are politically very stuck.”

Moreover, the COP29 climate-finance deal contains no pledge by developed countries to provide a set amount of public, bilateral finance, despite strong pressure from developing countries to include such a goal.

Following COP29, Thwaites released updated modelling to calculate different ways of reaching the $300bn target. He wrote: “What is clear is that $300bn by 2035 is eminently achievable, with little to no additional budgetary effort required from developed countries, let alone other contributors, to meet the goal.”

2. Developing-country contributions could cover part of the goal

Unlike the earlier $100bn target, contributions from developing countries could count towards the new climate finance goal.

Only developed countries are obliged to provide climate finance to developing countries under the Paris Agreement. But the NCQG outcome says that developing countries can “voluntarily” declare any climate-related funds they contribute, if they choose to do so.

This allowed negotiators at COP29 to skirt the controversial issue of formally expanding the list of official donors that are required to help with financial aid.

Developed countries had previously been pushing to enlist relatively wealthy developing nations, such as China and the Gulf states, to share the financial burden.

Several countries described since the early 1990s as “developing” under the UN’s climate convention are known to already make large, climate-related financial contributions to other developing countries. Examples include China’s Belt and Road initiative supporting clean-energy expansion and South Korea’s contributions to the GCF.

In fact, at COP29 China announced for the first time that it had “provided and mobilised” more than $24.5bn for climate projects in developing countries since 2017 — confirming that its contributions are comparable with those of many developed countries.

This roughly aligns with calculations by research groups that have placed China’s annual climate finance at around $4bn a year.

Both developed and developing countries pay money into MDBs. As well as “encouraging” developing countries to voluntarily contribute directly to climate finance, the NCQG outcome also specifies that these countries could start counting the share of climate-related money paid out of MDBs that can be traced back to their inputs.

Roughly, 30 per cent of the banks’ “outflows” can be attributed to developing countries in this way.

Counting the developing-country share of the projected increase in climate finance from MDBs by 2030 would add an extra $36bn to the global total, plus an extra $20bn of private finance mobilised by the funds.

It is not possible to say for sure how much climate finance new contributors such as China will choose to officially declare.

However, the chart below shows an estimate based on an “illustrative scenario”, by NRDC and others, of bilateral finance and multilateral climate funds, combined with expected MDB outflows and the associated private finance that this would mobilise. This could bring total annual climate finance up to $265bn by 2030.

Some observers at COP29 said they hoped that officially counting developing-country contributions towards UN “climate finance” targets would enable parties, such as the EU, to set more ambitious goals.

However, Michai Robertson, lead finance negotiator for the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), dismissed this as an “accounting trick”, because these funds are already being provided.

Li Shuo, head of the China climate hub at the Asia Society Policy Institute (ASPI), tells Carbon Brief that the NCQG outcome could bring more attention to China’s climate-related aid and lead to “stronger and better climate support from Beijing”. However, he notes that this is in the context of a low-ambition global target that is a “far cry” from what is needed: “I take this as a classic example of geopolitical competition weakening environmental ambition, namely, the geopolitical desire of including China as a donor without corresponding desire of developed countries to contribute more limited the overall scale of climate finance.”

3. Inflation wipes out much of the increase in climate finance

One issue that has surfaced in the wake of COP29 is the impact of inflation. Campaigners have noted that the failure to factor this into the 2035 climate-finance target means that, by the time it is met, the true value of the money pledged will be far lower than it is today.

In an article highlighting this issue, the Guardian reported that the $300bn goal was, therefore, “not the tripling of pledges that has been claimed”.

Researchers had flagged this before COP29, pointing out that the previous $100bn annually by 2020 goal, which was first set in 2009, had also not accounted for inflation.

They noted that merely correcting the $100bn for inflation would bring it to between $139bn and around $150bn a year. (Such calculations depend on the rate of inflation applied to the starting figure, as well as the base year for the calculation.)

Civil-society groups at COP29, such as Power Shift Africa, estimated that the impact of inflation would cut the “real” value of the $300bn to $175bn in today’s money by 2035. This is based on an annual inflation rate of five per cent.

In its analysis, the Guardian opted for an inflation rate of 2.4 per cent — based on the average rate in the US over the past 15 years. This is taken to reflect the conditions for governments contributing climate finance and the currency much of it would be provided in.

The figure below shows the impact of an inflation rate of three per cent. This is based on input from economists and analysis by the Center for Global Development (CGD), which, in turn, is based on the World Bank’s global GDP deflator.

If inflation over the next decade follows this trend, the $300bn pledged in 2024 would only be worth $217bn in today’s money in 2035 — a 28 per cent reduction in value.

In order to offer climate finance with a real value of $300bn in 2035, countries would have needed to set a goal for that year of around $415bn.

(The figures in the chart above cannot be directly compared with the existing pledges made by governments and MDBs, as those too would need to be adjusted for inflation.)

CGD modelling suggests that if developed countries’ climate-finance contributions simply increase in line with expected inflation and gross national income (GNI) growth, they would reach $220bn by 2035.

The CGD analysts write in a blog post that “by the time the new goal is met, beneficiary countries will find that the purchasing power of these resources has eroded significantly”.

Independent experts, as well as climate-vulnerable countries themselves, emphasised both before and during COP29 that more than $1tn dollars will be needed each year to help developing countries deal with climate change. Many developing nations said that around $600bn of this should come directly from developed countries’ public coffers.

With such a relatively small amount of finance pledged for the NCQG, some developing countries have already indicated that they may scale back their future climate ambitions.

This article was originally published by Carbon Brief on Dec. 3, 2024.

It is republished with permission under a Creative Commons licence.